Joburg Bar advocates seek to purge themselves of ‘oppressive’ payment system

Caption:

Joburg Bar advocates want their invoices to be paid within 30 days

📷 SUPPLIED

Advocates For Transformation (AFT), a lobby group championing the interests of previously marginalised advocates, has re-ignited a 10-year old battle to take down the disliked 97-day payment rule, which is only in force at the Johannesburg Bar.

This rule is widely criticised for financially harming up-and-coming previously marginalised advocates, primarily blacks and females, many of whom end up abandoning the profession to seek safe refuge in alternative full-time employment.

Advocates that support getting rid of the current payment system argue that they incur monthly chamber fees, bar fees, and living expenses, but their legal consulting fees are paid after 97-days and sometimes longer.

The critics of the 97-day rule further point out that some penny-pinching attorneys deliberately abuse it by making inexplicable late payments, worsening the cash-flow crunch experienced by newer members of the Johannesburg Bar, also known as Johannesburg Society of Advocates (JSA).

The JSA will hold an annual general meeting (AGM) on 23 October 2025, where a resolution tabled by AFT Johannesburg to end the 97-day rule will be put to vote by the members of JSA. AFT Johannesburg is chaired by well-known legal eagle, Advocate Tembeka Ngcukaithobi.

The resolution was taken after JSA conducted a survey in 2023, followed up by another ‘supplementary’ survey in 2025. The earlier survey had found that 88.33% of respondents wanted the JSA to scrap the 97-day rule, but it was never scrapped.

Roughly 11.67% of respondents are in favour of keeping the current system. The supplementary survey has only bolstered the first survey, and provided corroboration in the two years intervening.

Many respondents to the surveys want the current payment system to be reformed in favour of shorter payment periods. Unsurprisingly, there is clear preference for a 30-day payment cycle.

Other bars are operating on shorter payment periods compared to the Johannesburg Bar. Next door, the Pretoria Bar, already operates on a 30-day payment period, indicating that there is nothing preventing the Johannesburg Bar going the same route. The Cape Bar operates on a 60-day payment rule.

Another sticking point for disgruntled advocates is the manner in which many attorneys interpret the 97-day rule. They interpret it as a payment that must be made 97 days from the last day of the month in which the fees were earned. In some cases, attorneys count 97 days from the month in which the invoice was generated.

In other words, if an invoice for work done on 10 January is generated on 2 February, the attorneys will count 97 days from 28 February – meaning payment will be made on 7 June, more than five months after the work was completed.

The mismatch between the monthly expenses of advocates and the 97-days in which their invoices are paid creates a cash-flow strain.

There are concerns that attorneys are likely to resist attempts to scrap or change the current payment system because attorneys argue that it gives them a grace period to collect payments from clients.

However, advocates allege that the 97 day period enables wealthier attorneys to invest counsel’s monies and ‘earn millions of rands’ in interest. Alternatively, less wealthier attorneys dip into the trust account, and hope to make it up with future deposits received elsewhere, they say.

Furthermore, previously disadvantaged advocates worry that advocates who have amassed enough wealth at the Bar will resist change. These are advocates that would have consented to the rule many years ago, or those who enjoy regular briefs from attorneys to insulate them from disastrous consequences of the rule.

AFT suggests that a form of ‘gatekeeping’ is at play, hence the retention of a rule that evidently operates to the impoverishment of the JSA’s own members.

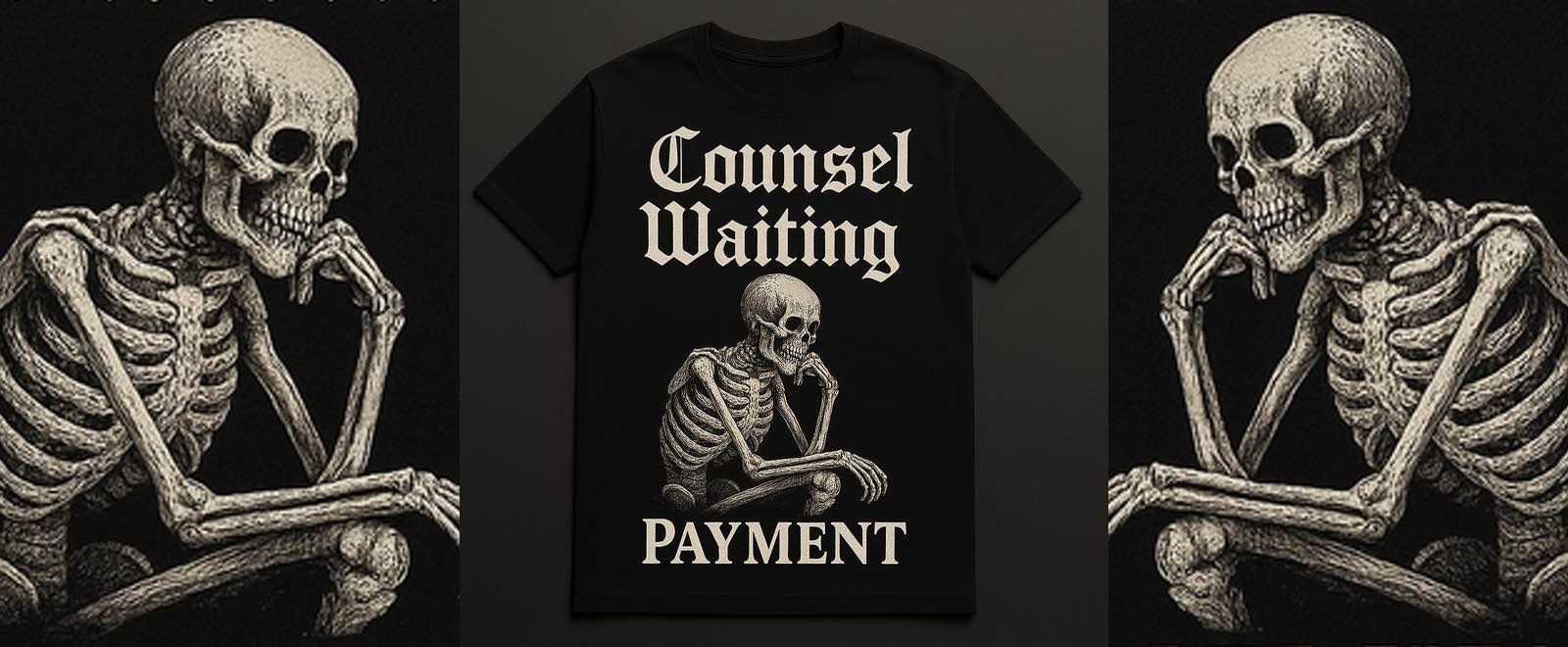

The campaign to take down the 97-day rule has gained momentum. Digital posters expressing strong opposition to the current payment system have started circulating on Whatsapp.

One poster read “97-day rule killing practice” and another poster with a drawing of a worried-looking human skeleton read “Counsel waiting (for) payment”.

The battle to scrap the rule dates back to 2015 when prominent Silk and transformation activist Vuyani Ngalwana spoke out against the rule, in an article titled “The Bar can no longer afford to play ‘Aunt Sally’ with transformation”, published in the Advocate magazine.

In the ‘Aunt Sally’ article, Ngalwana wrote that the 97-day rule and late payments of fees were responsible for high attrition rate amongst black members of the GCB.

“The attrition rate of many black members is attributable almost exclusively to poor cash flow which is exacerbated by the delay in the payment of Counsel’s fees by attorneys. Yet the Bar refuses to reconsider the oppressive 97-day rule in Johannesburg or 60-day rule in Cape Town and other constituent Bars,” wrote Ngalwana in the Advocate.

Ten years later, many more aspiring advocates still feel the squeeze at the JSA.

The calls for abolishment of the rule is part of a larger battle waged by black and female legal practitioners to transform the white male-dominated legal profession.

It has been raging since the late 1990s when senior legal practitioners like Ngalwana and Norman Arendse made proposals for transforming the sector.

But lobby groups representing black legal practitioners like Black Lawyers Association (BLA), and Pan African Bar Association of South Africa (PABASA) say progress is slow due to resistance to transformation.

High entry barriers still keep black people out or drive them out. Those that remain inside the profession are starved of getting complex and lucrative briefs from clients and instructing attorneys.

The likes of AFT, BLA, and PABASA point to the ongoing lawsuit by top law firm Norton Rose Fulbright SA (NRFSA) to block the legal sector’s new Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) targets as proof of resistance to transformation.

The new B-BBEE targets, known as the Legal Sector Code (LSC), gazetted in September last year, replaced generic B-BBEE targets that failed for nearly two decades to transfer a fair amount of the sector’s wealth into the hands of black legal practitioners.

The bone of contention for NRFSA is that the LSC’s targets for black ownership and preferential procurement are unreasonable and unattainable as they are higher than the targets in the B-BBEE generic code.

Research findings made public in 2023 by the Legal Practice Council (LPC) conclusively show that blacks and females are struggling to build law firms that are capable of competing with large white-owned firms.

This is because black lawyers have limited access to steady flow of quality instructions compared with the so-called Big Five Sandton law firms: Bowmans, Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, ENSafrica, Webber Wentzel, and Werksmans, which get a lion’s share of lucrative work from clients. These firms, in turn, are accused of briefing mainly white male Silks.

To add salt to injury, when black legal practitioners received instructions, they were often restricted to performing inferior peripheral work while whites enjoyed specialised and lucrative work.

These skewed and discriminatory briefing patterns resulted in blacks being over-represented in the provision of legal advice in matters involving labour, crime, matrimonial, and Road Accident Fund (RAF) claims.

Black lawyers are under-represented in commercial law, where mostly whites offer legal advice in areas such as banking, tax, intellectual property, corporate finance, mergers & acquisitions, asset restructuring, competition law, insolvency and business rescue, aviation and maritime law.

It remains to be seen if JSA is ready to take the step, and eliminate what appears to be a patently ‘anti-transformational rule’.