Can ‘Born Frees’ escape poverty that held their parents hostage?

Caption:

Stats SA’s latest income and expenditure survey (IES)

confirms that South Africa is an unequal society.

📷 NL-GRAPHICS DEPT

Most parents dream of their children to out-earn them. Not just out-earn them by a small margin, but by a long mile. But in some parts of the world, wealth and income inequality is so stubbornly entrenched to a point where entire families and generations are trapped in either economic hardship or poverty.

In a country like South Africa, the world’s most unequal society, poverty entrapment and slow or lack of upward social mobility are a daily reality for many people. Stats SA recently published its latest income and expenditure survey (IES), which provided yet another piece of evidence of the existence of huge income inequality between black and white South Africans.

This means that wealth redistribution measures such as welfare grants, affirmative action, and black economic empowerment (BEE) that government has implemented since the end of apartheid in 1994 are failing to close the income gap. If anything, the majority of black Africans are still languishing at the bottom of the income ladder.

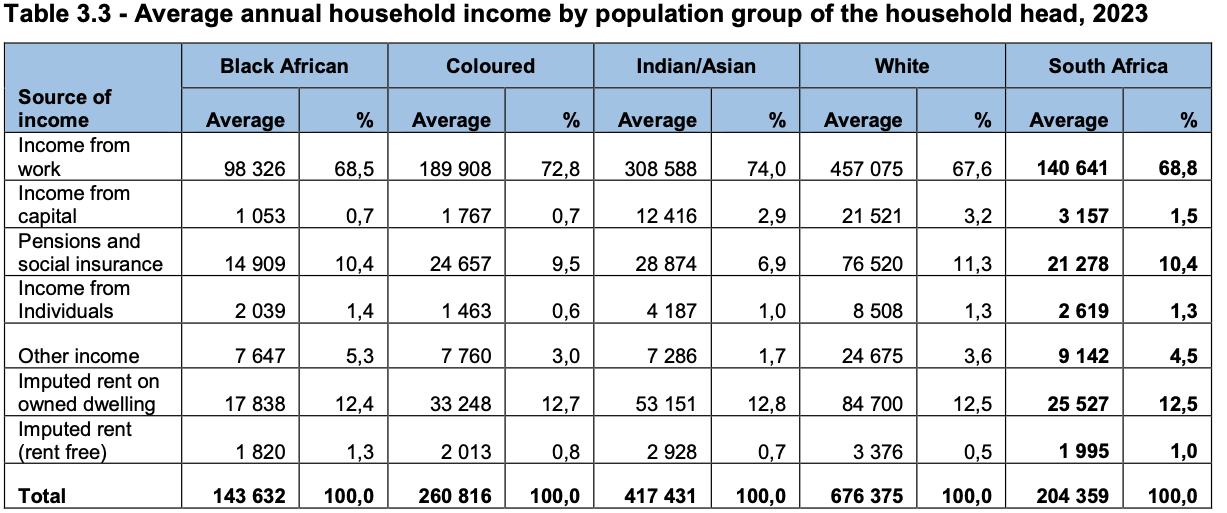

According to the IES, the top 10% of households earned about 50.6% of all the country’s total household income while middle-income homes earned around 42%. White households were by far the highest earners in 2023, earning an average income of about R676 375 annually. This is almost five times higher than the average annual income of black African households, which was R143 632 in 2023.

Table 3.3

- Page 28

📷 STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA

White families also earned almost three times higher than the coloured families, which earned R260 816 annually. At the second spot on the income ladder behind white families are Indian households, which earn R417 432 annually.

📷 NL-GRAPHICS DEPT

The IES also revealed that nearly half of black African homes were living on pittance monthly. About 45,1% of black African homes either earned up to R1 173 per month or R2 286 per month.

So it came as no surprise when the IES revealed that black African households were not only out-earned by households of whites, coloureds, and Indians, but were also outspent by these three population groups, which combined made up 19% of the South African population compared with black Africans, who accounted for 81% of the population. The survey shows that South African households spent approximately R3 trillion between November 2022 and November 2023.

From the survey’s results, it is clear that thirty years into our country’s democracy there hasn’t been significant trickle down of wealth to the majority of black African families. As a country, we are far away from achieving equitable wealth distribution or even remotely building an egalitarian society.

This failure to equitably redistribute wealth means that a large number of black African “Born Frees,” who were born after 1994’s first democratic elections -- which officially ended apartheid -- are not enjoying the fruits of democracy.

Far from benefiting from the so-called ‘democratic dividend’, they are trapped in unemployment, as opposed to low-paying mining and factory jobs that their parents and grandparents accessed to keep hunger at bay.

The parents and grandparents of black “Born Frees”, many of whom were born after the end of Second World War in 1945, lived through apartheid introduced in 1949. Most black Africans cannot relate to Western constructs such as “Baby Boomers” (born between 1946 and 1964), Gen X (born between 1965 and 1980), and Gen Y or Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) because they were excluded from owning land and businesses in major industrial and commercial cities.

This prevented them from building wealth, which they could pass down to their ‘Born Free’ children and grandchildren, many of whom are the contemporaries of Gen Z, born between 1997 and 2012. Many ‘Born Frees’ are afflicted by youth unemployment, which is currently at a staggering 45.5% -- well above the national average of 32,1%.

Based on the results of Stats SA’s IES, it is quite obvious that white Baby Boomers, and their Gen X and Millennial children are still well-off in post-apartheid South Africa. It is also safe to conclude that white Baby Boomers have been passing down wealth to their children while their black African peers have not been doing so.

The Western world is also grappling with inter-generational wealth inequality, even though not racialised as is the situation in our country. Millennials are generally worse off than Baby Boomers and Gen Xers.

This is because Gen Xers are mostly at the age where they are more likely to be either in higher-paid jobs or in senior leadership roles while Baby Boomers accumulated wealth on the back of investing in stock markets and buying real estate.

The Baby Boomers have accumulated so much wealth to a point they are considered the richest generation ever, thanks to a strong surge in property and share prices. On the other hand, Millennials and older Gen Zers, have struggled due to exposure to high levels of debt and inability to purchase exorbitantly-priced homes.

However, Baby Boomers are expected to pass down wealth to their Gen X and Millennial children over the next two decades. Last year, Boston-based consulting firm Cerulli Associates estimated that the world’s ultra-wealthy will transfer an estimated $124 trillion in assets by 2048, primarily to heirs and charities, with Baby Boomers and older generations expected to transfer 81% of this wealth.

Unfortunately this wealth transfer won’t trickle down to most black African ‘Born Frees’. So how do you move ‘Born Frees’ up the income ladder to enable them escape the poverty that once held hostage their parents and grandparents?

French economist Thomas Piketty, author of the best-selling book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, recommends that the best way to close economic inequality is to levy a global wealth tax and progressive income taxes.

But South Africa needs more than just redistributive taxes to tackle its wealth and income gap. It needs to grow the size of its economic pie to produce more slices to pass around amongst its citizens. To increase the economic pie, we must attract high levels of fixed investment and upgrade our skills base. If we do so, the ‘Born Frees’ stand a chance of escaping poverty through accessing decently-paying jobs or owning companies that generate new wealth.

Higher incomes will enable them to save and invest. This way the ‘Born Frees’ can start being on a journey to increase their share of national income either as owners of labour or capital, giving them room to build wealth for themselves and their descendants.